Middle Ground

Over Middle Ground

Middle Ground (of “Tussenweg”) is een educatieve online applicatie die leerlingen en studenten aanzet tot het gezamenlijk ontwikkelen van een goed beredeneerd compromis dat een maatschappelijke kwestie zou kunnen beslechten. Compromissen, waarbij de deelnemers op basis van wederzijdse concessies tot overeenstemming komen, zijn van groot belang voor samenleving en politiek. Compromissen, waarbij de deelnemers op basis van wederzijdse concessies tot overeenstemming komen, zijn van groot belang voor samenleving en politiek. Met Middle Ground kunnen leerlingen en studenten een eigen perspectief ontwikkelen op de voor- en nadelen van compromisvorming, ervaringen opdoen met deliberatief onderhandelen, en hun vaardigheden op het gebied van gespreksvoering en burgerschap verfijnen. Naast deze online applicatie bestaat er tevens een offline versie van de Middle Ground applicatie.

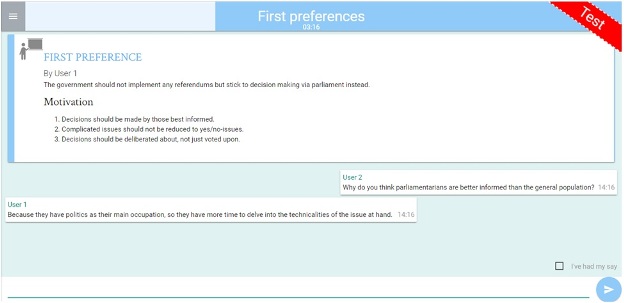

Voor verdere informatie over Middle Ground - de handleiding, de leerdoelen, de achtergrond van de methode en hoe je je kan aanmelden - lees verder of gebruik het menu aan de rechterkant van de pagina. Hieronder een voorbeeld van de 'eerste voorkeuren' fase (één van de in totaal drie fasen).

About Middle Ground

Middle Ground is an educational online application which encourages students to cooperate on the joint development of a well-reasoned compromise which could settle a social issue. Compromises, whereby the participants reach an agreement on the basis of mutual concessions, are of great importance to society and politics. With Middle Ground, students can develop their own perspective on the advantages and disadvantages of compromising, gain experience with deliberative negotiations, and refine their skills in the field of conversation and citizenship. In addition to this online application, there also exists an offline version of the Middle Ground application.

For more information about Middle Ground - the user guide, the learning objectives, the background of the method, and how to sign up read on or use the menu on the right side of this page. Below an example of the "first preference" stage (one of the three stages)

Afbeelding: screenshot van de Middle Ground webapplicatie Image: screenshot of the Middle Ground webapp

Hoe werkt de Middle Ground applicatie?

In de rol van beheerder voert de docent een maatschappelijk of politiek vraagstuk in. Bijvoorbeeld: “Moet de overheid paal en perk stellen aan het gebruik van sociale media door jongeren onder de 16?” Zonder pressie geen concessie, dus de docent voert eveneens een (fictief) scenario in, zoals een scenario waarin de deelnemers samen een bestuur vormen dat op basis van unanimiteit minus één binnen 90 minuten een beleidsplan moeten ontwikkelen. Als het aanmaken van de nieuwe sessie is voltooid, ontvangt de docent een code waarmee de leerlingen of studenten kunnen inloggen. De deelnemers voeren de discussie vervolgens online en in real-time.

Middle Ground leent zich voor het bespreken van politieke of maatschappelijke vraagstukken, met name als die uiteenlopende meningen en gevoelens oproepen. Op basis van een transparante en niet-manipulatieve uitwisseling van redenen proberen de deelnemers een resultaat te bereiken dat recht doet aan hun uiteenlopende gezichtspunten.

De deelnemers delibereren in groepen van twee tot maximaal vijf personen over het vraagstuk. Eerst nemen ze hun standpunten in en leggen ze elkaar hun beweegredenen uit. Dan ontwikkelen en beargumenteren ze compromisvoorstellen. Tenslotte proberen ze in een onderhandelingsspel tot een redelijk compromis te komen.

Voorbeelden van politieke of maatschappelijke vraagstukken zijn:- - Willen we gender quota invoeren in het bedrijfsleven?

- - Welk soort referendum kiezen we?

- - Mogen hoofddoekjes in het onderwijs?

- - Moet de EU-Turkije deal over vluchtelingen verlengd worden?

- - Hoe moeten de taken verdeeld worden bij een groepsopdracht?

- - Hoe verdelen we het feestbudget?

Voor meer informatie, raadpleeg een van de onderstaande handleidingen.

- Handleiding voor de Middle Ground applicatie, inclusief voorbeeld Engels | Nederlands

- Handleiding voor de offline versie van Middle Ground Engels | Nederlands

How does the Middle Ground application work?

The teacher, in the role of admin, introduces a social or political issue. For example: “Should the government impose limits on the use of social media by young people under 16?” Without pressure no concession, so the teacher also introduces a (fictitious) scenario, such that the participants together form a board that on the basis of unanimity minus one should develop a policy plan within 90 minutes. When the creation of the new session is complete, the teacher receives a code that allows students to log in. The participants then conduct the discussion online and in real time.

Middle Ground lends itself for discussing political or social issues, particularly when they evoke differing opinions and feelings. On the basis of a transparent and non-manipulative exchange of arguments, the participants try to achieve a result that does justice to their different points of view.

The participants deliberate in groups of two to a maximum of five persons about an issue. First they take their positions and explain their motives to each other. Then they develop and substantiate compromise proposals. Finally, they try to reach a reasonable compromise in a negotiation game.

Examples of political or social issues are:- - Do we want to introduce gender quotas in businesses?

- - Which kind of referendum do we choose?

- - Should we allow people to wear headscarves in educational settings?

- - Should the EU-Turkey deal concerning refugees be extended?

- - How should different tasks be divided for a group assignment?

- - How should we divide a party budget?

For more information, consult one of the user guides below.

Waar is Middle Ground voor geschikt?

De applicatie vormt een aanvulling op het debatteren en discussiëren dat onderdeel uitmaakt van veel curricula, en is te gebruiken voor verschillende leerdoelen. Voorbeelden hiervan zijn:

- 1. Vaardigheden ontwikkelen voor op samenwerking gerichte argumentatie, gespreksvoering, luisteren en probleemoplossing.

- 2. Het opdoen van kennis van de voorwaarden voor vruchtbare onderhandelingen.

- 3. Een eigen perspectief ontwikkelen op de voor- en nadelen van het sluiten van een compromis.

- 4. Inzicht verkrijgen in (historische of actuele) maatschappelijke kwesties en politieke processen.

- 5. Het verminderen van polarisatie en groepsdenken.

- 6. Het verhogen van morele en ideologische gevoeligheid, empathie, compromisbereidheid en integriteit.

Middle Ground is geschikt als werkvorm in de lessen maatschappijleer en burgerschapsvorming op het VO en het MBO, en als module in HBO en WO cursussen waarin kritisch denken, academische vaardigheden of collectieve besluitvorming tot de leerdoelen behoort.

De offline versie van de Middle Ground methode is reeds toegepast aan verschillende faculteiten van de Rijksuniversiteit van Groningen in vakken over academische vaardigheden, bedrijfsethiek, argumentatieleer, leiderschapsvaardigheden en industrieel ontwerpen. Daarnaast is de methode toegepast in het vak maatschappijleer op middelbare scholen in Nederland.

For which purposes is Middle Ground suitable?

The application provides a tool that complements existing tools for debating and discussion which are already part of many curricula. Middle Ground can be used for several learning objectives. Examples are:

- 1. Developing skills for cooperative argumentation, conversation, listening and problem solving.

- 2. Obtaining knowledge about the conditions for fruitful negotiation.

- 3. Develop one's own perspective on the advantages and disadvantages of reaching a compromise.

- 4. Gain insight into (historical or topical) social issues and political processes.

- 5. Reducing polarization and group thinking.

- 6. Increasing moral and ideological sensitivity, empathy, spirit of compromise, and integrity.

Middle Ground is suitable as a teaching method in social studies and civic education at secondary school and secondary vocational education, and as a module in higher professional education or university education courses in which critical thinking, academic skills or collective decision making is among the learning objectives.

The offline Middle Ground method has been applied at several faculties of Groningen University, The Netherlands, in courses on academic skills, business ethics, philosophy of argument, leadership skills, and industrial engineering. Furthermore, the offline version of the method has been applied to social science courses at Dutch secondary schools.

Achtergrond

De Middle Ground applicatie bouwt voort op reeds bestaande educatieve methodes, waaronder methodes voor kritisch denken (e.g. Fischer, 2011) en voor debatteren en discussiëren (e.g. Kuhn, 2005; Hess, 2009). Geïnspireerd door de deliberatieve wending in de politieke filosofie (Elster, 1995; Habermas, 1996; Rawls, 2005), zijn er verschillende praktische procedures voor opinievorming en deliberatieve besluitvorming ontwikkeld, waaronder "deliberative polls" en "town hall meetings" (Fung, 2003; Fishkin, 2009). De Middle Ground methode bouwt daarnaast voort op een recente beweging om deliberatief onderhandelen in beleidsontwikkeling te bestuderen (Mansbridge et al., 2010; cf. Steiner et al., 2004; cf. Weinstock, 2013; cf. Wendt, 2016).

Mensen hebben vaak een tweeslachtige houding ten aanzien van compromissen in het persoonlijke, sociale en politieke leven (Benjamin, 1990; Margalit, 2010). Middle Ground biedt de mogelijkheid om een compromisoplossing te ontwikkelen in situaties waarin de betrokken partijen het blijvend met elkaar oneens zijn, en er dus geen echte inhoudelijke overeenkomst bereikt kan worden, maar waarin ze toch bereid zijn op basis van geven en nemen een akkoord te sluiten (van Laar en Krabbe, 2018a). Een Middle Ground discussie levert de deelnemers een aanknopingspunt om na te denken over de voor- en nadelen van compromisoplossingen.

De eerste twee fasen van de procedure van Middle Ground zijn gericht op het aanmoedigen van diversiteit, terwijl de derde fase gericht is op overeenstemming (cf. Sunstein & Hastle, 2015). Deelnemers redeneren en argumenteren, maar niet om elkaar te overtuigen van de juistheid van hun voorkeursoplossing, maar aanvankelijk om uit te leggen wat hen motiveert en uiteindelijk om uit te vinden of er een tussenoplossing is die voor de deelnemers acceptabel is (van Laar en Krabbe, 2017, 2018a, 2018b; cf. Holzinger, 2004; cf. Amgoud and Prade, 2006; cf. Fischer, Ury, and Patton, 2011). Op deze wijze proberen ze een uitkomst te bereiken die aan twee eisen voldoet (Raiffa, Richardson, and Metcalfe, 2002). Ten eerste verkiest elke deelnemer de gekozen compromisoplossing ten opzichte van de status-quo (het 'no deal'-scenario zonder compromis). Ten tweede zien de deelnemers geen mogelijkheid om de compromisoplossing te verbeteren met instemming van anderen.

Background

The Middle Ground application builds on already existing educational resources, including methods concerning critical thinking (e.g. Fischer, 2011) and debate or discussion-oriented education (e.g. Kuhn, 2005; Hess, 2009). Inspired by the deliberative shift in political philosophy (Elster, 1995; Habermas, 1996; Rawls, 2005), different practical procedures for opinion formation and deliberative decision making have been developed, including deliberative polls and town hall meetings (Fung, 2003; Fishkin, 2009). The Middle Ground method builds furthermore on a recent trend to study deliberative negotiation in legitimate policy making (Mansbridge et al., 2010; cf. Steiner et al., 2004; cf. Weinstock, 2013; cf. Wendt, 2016).

People often have an ambivalent attitude towards compromises in the personal, social en political life (Benjamin, 1990; Margalit, 2010). Middle Ground offers the possibility to develop a compromise agreement in situations in which no substantive consensus is feasible, yet where the participants are prepared to look into a compromise solution on the basis of give and take (van Laar en Krabbe, 2018a). A Middle Ground session thus provides students with leads for the reflection about the pros and cons of compromise solutions.

The first two parts of the procedures of Middle Ground aim at encouraging diversity, whereas the third aims at an agreement (cf. Sunstein & Hastle, 2015). Participants reason and argue, yet not to convince others of the correctness of their firstly preferred solution, but at first to explain what motivates them and in the end to find out what middle ground solution, if any, would be mutually advantageous (van Laar en Krabbe, 2017, 2018a, 2018b; cf. Holzinger, 2004; cf. Amgoud and Prade, 2006; cf. Fischer, Ury, and Patton, 2011). In this way, they try to arrive at an outcome that meets two requirements (Raiffa, Richardson, and Metcalfe, 2002). First, each participant prefers the chosen compromise solution to the status quo (the ‘no-deal’ scenario without compromise). Secondly, the participants see no possibility of improving the compromise solution with the consent of others.

-

expand_moreReferenties en achtergrondartikelenReferences and background articles

- Amgoud, Leila, and Henri Prade (2006). Formal Handling of Threats and Rewards in a Negotiation Dialogue. In: Argumentation in Multi-Agent Systems: Second International Workshop, ArgMAS 2005, Utrecht, The Netherlands, July 26, 2005: Revised Selected and Invited Papers, ed. by Simon Parsons, Nicolas Maudet, Pavlos Moraitis, and Iyad Rahwan, 88-103. Berlin: Springer.

- Benjamin, Martin (1990). Splitting the Difference: Compromise and Integrity in Ethics and Politics. Lawrence KS: University of Kansas.

- Elster, Jon (1995). Strategic uses of argument. In: Kenneth J. Arrow, Robert H. Mnookin, Lee Ross, Amos Tversky, and Robert B. Wilson (Eds.). Barriers to Conflict Resolution. (pp. 236-57). New York: Norton.

- Fisher, Alec (2011). Critical Thinking: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fisher, Roger, William Ury, and Bruce Patton (2011). Getting to Yes: Negotiating an Agreement without Giving In, 3rd ed. London: Random House.

- Fishkin, James S. (2009). When the People Speak: Deliberative Democracy and Public Consultation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Fung, Archon (2003). Recipes for Public spheres: Eight institutional design choices and their consequences. Journal of Political Philosophy, 338-367.

- Gutmann, Amy, and Dennis Thompson (2012). The Spirit of Compromise: Why Governing Demands It and Campaigning Undermines It. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Habermas, Jürgen (1996). Between Facts and Norms. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hess, Diana E. (2009). Controversy in the Classroom: The Democratic Power of Discussion. New York: Routledge.

- Holzinger, Katharina (2004). Bargaining through arguing: An empirical analysis based on speech act theory. Political Communication, 21, 195-222.

- Kuhn, Dianna (2005). Education for Thinking. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- van Laar, Jan Albert, and Erik C. W. Krabbe (2018a). Splitting a Difference of Opinion: The Shift to Negotiation. Argumentation, 32, 329-350.

- van Laar, Jan Albert, and Erik C. W. Krabbe (2018b). The Role of Argument in Negotiation. Argumentation, 32, 549-567. Online first, doi: 10.1007/s10503-018-9458-x.

- van Laar, Jan Albert, and Erik C. W. Krabbe (2018c). Criticism and Justification of Negotiated Compromises. Journal of Argumentation in Context, 8, 1, 91-111.

- Mansbridge, Jane, James Bohman, Simone Chambers, David Estlund, Andreas Follesdal, Archon Fung, Christina Lafont, Bernard Manin, and José Luis Martì (2010). The Role of Self-Interest and the Role of Power in Deliberative Democracy. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 18, 64-100.

- Margalit, Avishai (2010). On Compromise and Rotten Compromises. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Raiffa, Howard, John Richardson, and David Metcalfe (2002). Negotiation Analysis: The Science and Art of Collaborative Decision Making. Cambridge MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Rawls, John (2005). Political Liberalism (Expanded edition). New York: Columbia University Press.

- Steiner, Jürg, André Bächtiger, Markus Spörndli and Marco R. Steenbergen (2004). Deliberative Politics in Action. Analysing Parliamentary Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sunstein, Cass, and Reid Hastie (2015). Wiser: Getting Beyond Groupthink to Make Groups Smarter. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Wendt, Fabian (2016). Compromise, Peace and Public Justification: Political Morality Beyond Justice. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Weinstock, Daniel (2013). On the possibility of principled moral compromise. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 16(4), 537-556.

Aanmelden

Om gebruik te maken van de Middle Ground online applicatie is een account vereist. Stuur daartoe een bericht naar Jan Albert van Laar (mail_outline j.a.van.laar@rug.nl). Na ontvangst van het wachtwoord kunt u vervolgens via de knop 'Login beheerder/admin' bovenaan deze pagina gebruikmaken van de Middle Ground applicatie. Voor het gebruik van de offline versie is geen account vereist. Raadpleeg de handleiding voor verdere informatie over het gebruik van Middle Ground. Het gebruik van de Middle Ground applicatie is gratis voor docent en student.

Voor verdere vragen, op- of aanmerkingen en feedback op de applicatie kunt u tevens via e-mail terecht bij Jan Albert van Laar.

Sign Up

To use the Middle Ground online application an account is required. Send a message to Jan Albert van Laar (mail_outline j.a.van.laar@rug.nl) to acquire a username and password. After receiving this you can use the Middle Ground application via the ‘Login admin’ button at the top of this page. No account is required for the use of the offline version. Consult the user guide for further information on the use of Middle Ground. The use of the Middle Ground application is free for teacher and student.

You can also reach out to Jan Albert van Laar via email for further questions, comments, remarks, and feedback on the application.

Andere methodes

Voor vergelijkbare methodes op het gebied van redelijk argumenteren of deliberatie, zie de onderstaande links.

Other Methods

For several other methods concerning argumentation, view the links below.

Ontwikkelingen

Met een Comeniusbeurs (senior fellow) richten we ons op twee uitbreidingen.

- 1. We ontwikkelen een app voor "deliberatief debatteren" die de deelnemers aanmoedigt te argumenteren, om kritisch te evalueren en om hun positie te verbeteren. De app is gericht op het reflecteren op woordkeus en voorbeelden ("framing"), op het beoordelen van bronnen (contra nepnieuws en informatiebubbels) en op het erkennen van de waarde van bezwaren.

- 2. We ontwikkelen een app voor "deliberatief ontwerpen." Een bedieningspaneel stelt een docent of gevorderde student in staat zelf een discussieformat te ontwerpen, waarna deelnemers uitgenodigd kunnen worden voor dat type discussie. De app maakt het mogelijk om op basis van gebruikerservaringen stapsgewijs een discussieformat te ontwerpen dat past in een bepaald curriculum, maar ook om te experimenteren met de vormgeving van de digitale publieke ruimte.

Future developments

- 1. We develop an app for ‘deliberative debate’ that encourages participants to argue, to critically evaluate, and to improve their position. The app encourages the participants to reflect on the choice of words and examples (‘framing’), on the assessment of sources of information (counter fake news and information bubbles), and on the acknowledgement of the value of criticisms and objections.

- 2. We develop an app for ‘deliberative design’. A control panel allows teachers or advanced students to design a discussion format themselves, after which participants can be invited to that type of discussion. The app makes it possible to design, on the basis of user experiences, step by step a discussion format that fits a specific curriculum, but also to experiment with the design of the digital public space.